in conversation with . . .

KiM MUPANGILAÏ

Kim Mupangilaï in East Williamsburg, Brooklyn

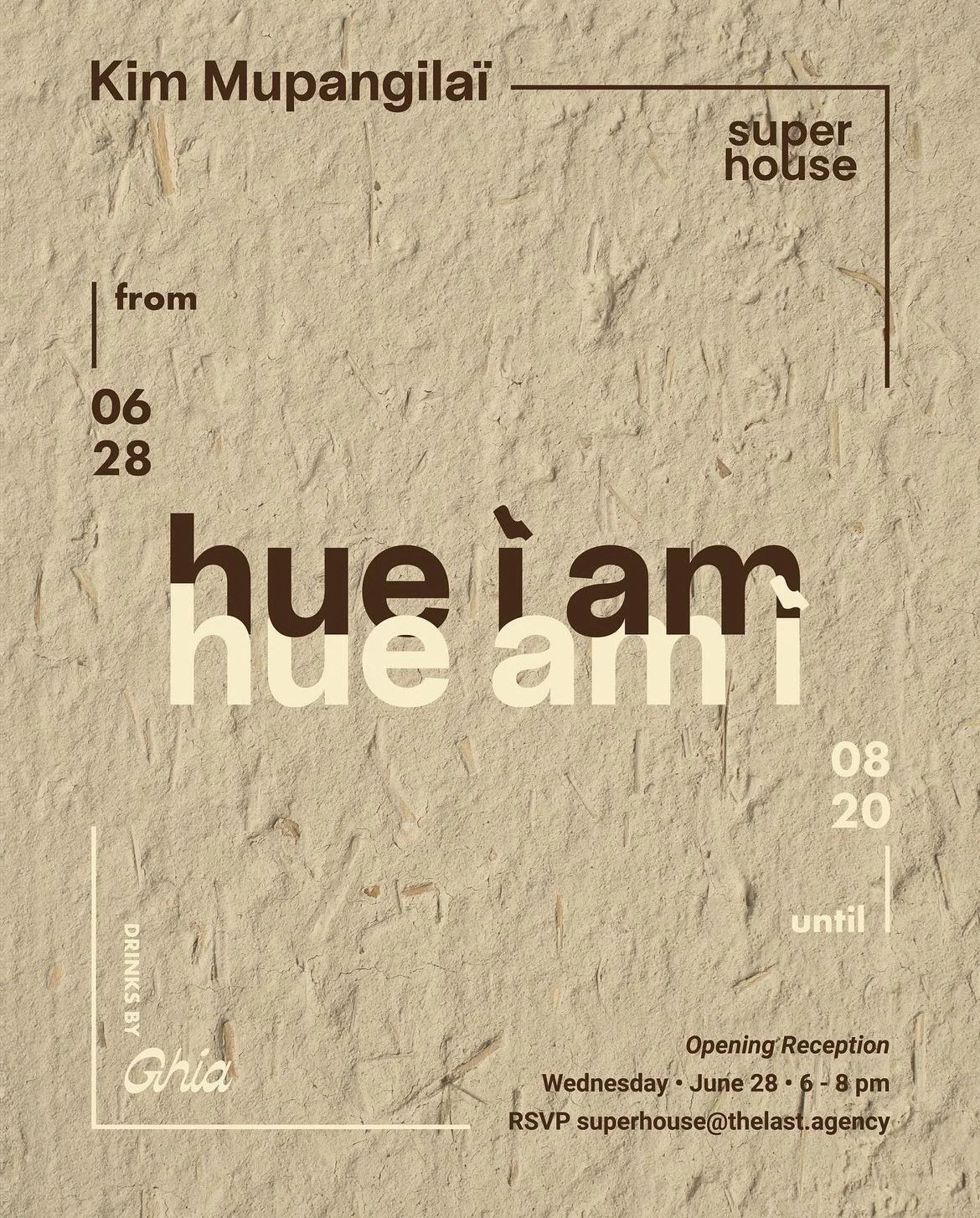

Kim Mupangilaï is an interior architect and furniture designer practicing in New York. After a career in residential and retail interiors, working on projects, including Greenpoint’s beloved Ponyboy bar, she branched out into furniture design. Her debut furniture collection, Kasaï, was on display last year in her solo exhibition Hue I Am / Hue Am I at Superhouse.

The shapes and materiality of her whimsical pieces draw inspiration from her Belgian Congolese heritage.

Mupangilaï continued her collaboration with Superhouse at Design Miami 2023, where she displayed additional furniture designs that tied perfectly into the year’s curatorial theme, “Where We Stand”: “A celebration of objects inspired by place, identity, and heritage.” Most recently, her sculptural chair, Bina, was acquired by Vitra Design Museum.

Keep in touch with Eftihia:

Instagram

@pangilai

Gallery Representation

www.superhouse.us

Words by: Tina Iasonidis

Photos by: Tina Iasonidis, unless otherwise noted

Interview recorded:

Pieces from the Kasaï furniture line at Kim’s solo exhibition Hue I Am / Hue Am I

In your own words, who are you, and what do you do?

I am Kim. I am a Belgian Congolese interior architect and designer. And I am a creative living in New York. I design spaces―residential and commercial. I have recently brought out my first furniture series.

Why design?

I went to school for graphic design and interior architecture, so it definitely came from that.

But if I go back to my younger years, I think it came about through my grandparents. I was always going up the attic and looking at old things, and still am a huge fan of vintage pieces. My granddad is like a handyman; he was always making something in his shop. I think it kind of birthed my love for design and creation. That’s kind of when I decided to study it, really, and get degrees in it.

How did your upbringing influence the way you think about and experience design?

I think that’s a tough one. I grew up in Europe―Belgium. I think the way I experienced design was very conventional, very single-minded. But then when I came to New York, surprisingly, it kind of changed. Because New York is so diverse, and it’s like a melting pot of different cultures, I started to kind of dig deeper into design history and read more about it, and also dig deeper in my own cultural landscape.

I think it’s hard to name one word of how I experience design, but I think it’s kind of the same as people: it’s like a melting pot of creations and different cultures and countries. It can be whatever you want it to be. And it can be influenced by a lot.

I feel like I see design in everything. It doesn’t necessarily need to be something tangible, but I feel like if I go on a walk, I see things that relate to design. If I look through magazines, I see things that relate to design. So it can mean anything.

I THINK IT’S HARD TO NAME ONE WORD OF HOW I EXPERIENCE DESIGN, BUT I THINK IT’S KIND OF THE SAME AS PEOPLE: IT’S LIKE A MELTING POT OF CREATIONS AND DIFFERENT CULTURES AND COUNTRIES. IT CAN BE WHATEVER YOU WANT IT TO BE. AND IT CAN BE INFLUENCED BY A LOT. I FEEL LIKE I SEE DESIGN IN EVERYTHING.

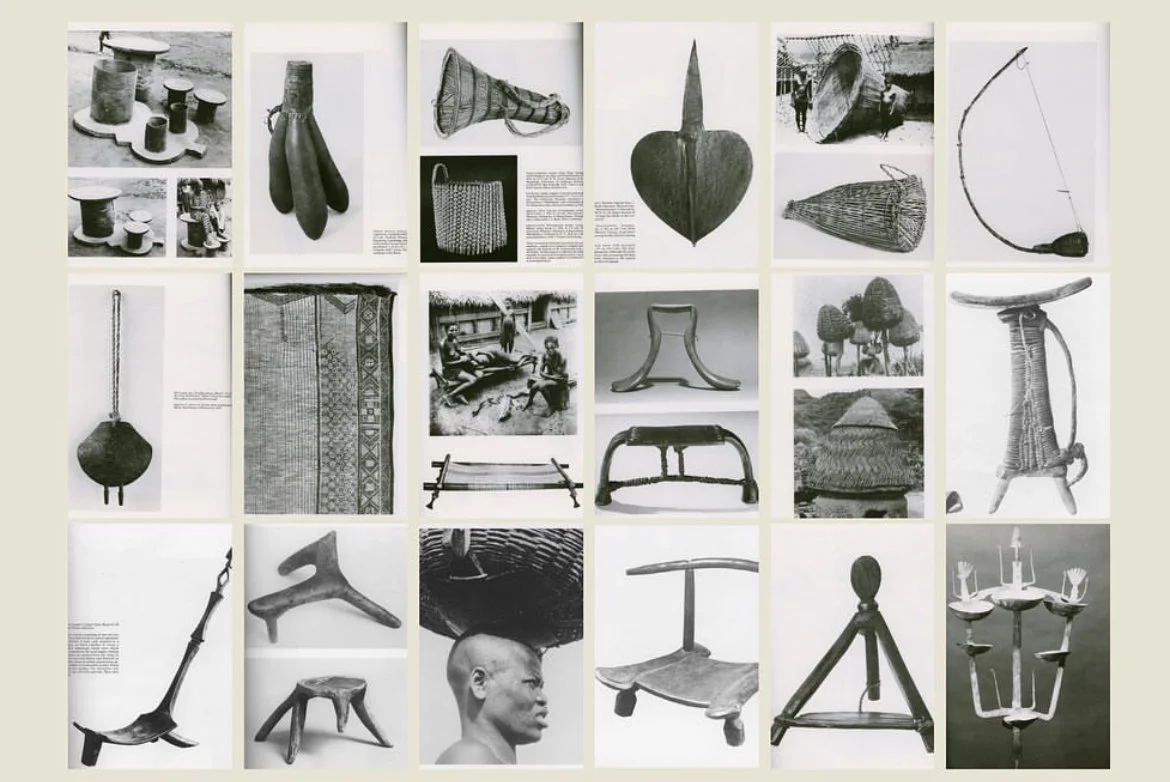

Scanned collages by Kim of Congolese art, architecture, and objects that serve as inspiration studies

How did the different places you studied in and lived in inspire you?

It was very conventional art history. They weren’t really speaking on colonialism within art and design. And about cross-cultural design or cultural appropriation. None of my professors talked about that. So in that sense, I felt kind of brainwashed because as a mixed-race kid, I was like, Oh OK, so everything comes from, I guess, Belgium, or Europe, but not at all.

Later in life, I came to New York, and then digging into my own cultural heritage, understanding that there’s so much more to it. So in that sense, it influenced me, knowing the general stuff about art and design, but definitely not everything. There’s so much more to it. I feel like maybe professors left that out deliberately, or they weren’t educated themselves enough. And I think that’s something I would love to see change in the education system in general, for future students.

I think that those conversations probably only started happening more in earnest in the last five years in academia . . .

Exactly. Exactly.

When I was studying art history, I feel like that wasn’t really touched on. At NYU, you would think they would . . . when I was studying, you weren’t hearing much.

Exactly! And I felt kind of displaced in all of that. And that’s also what a panel talk [I was part of] was about― expanding on that, and talking with other people in the crowd about that, asking how they experience that. To me, the educational part about design and artistry is so crucial and important before you become a designer, so you start with the right intentions. In that sense, I was kind of disappointed in the education system, but at the time itself, I didn’t realize because I didn’t know.

What is your form of self expression?

These pieces of furniture.

I’m discovering my identity more, my heritage, and I’m pushing it out through furniture as opposed to speaking about it. To me, that’s a great weight because I’m still discovering and still learning, and I think it will never stop.

What brought you to New York?

I guess for a lot of people coming from a small country, they’re like, There must be more to it, I want to explore different countries. I think I always felt like I wasn’t going to stay in one place. I wanted to explore. After I graduated, I backpacked solo for the first time for three months, and I met some New Yorkers. They said, “If you ever want to come to New York, you can always stay with me.” I took them up on that offer.

While I was studying, I thought, Wouldn’t it be amazing to have an experience in New York, the city of culture and diversity and creativity? And I was like, Perfect, I’m going to. I came to New York in 2017 and was like, I’m just going to throw myself in front of the lions, knock on every door, go to all these design fairs, send my portfolio to everyone, and see what comes out of it. And that’s kind of how it started. Now I’m still here! Five and half years later [laughs].

Armoire from the Kisaï line

When you came to New York, were you practicing as an interior designer or interior architect?

Yes. Exactly. That was two years after I graduated, and I was on a visa that allowed me to work for an architecture and design company. That’s when I realized also, Oh my god, there’s literally so little money to make . . . The hours. The time. When I started at that architecture and design firm, I was making $12 an hour. And I was living here in Bushwick with three other roommates. My bedroom was, in 2018, $1,100. OK, I might as well explore the dollar store, because I was on such a tight budget. I was like, This is insane. New York is already so expensive.

How did you launch this career? I know your background started in graphic design, interior architecture, and now it’s entering more furniture.

Design, architecture, interiors―I was always in awe of it. And I always want to do something with it. And I did. Like I said, I did work for a firm, and then I had some solo projects as well. But I did them all on my own and I realized, Holy shit, doing the project management, doing the whole design, it’s a lot. Since I was, I think, sixteen, I always wanted to make my own chair, or a table, this or that. In school, we had one project where we could make it. I was like, This is so fun. And I think later in life, I will probably end up doing something like that.

But then the pandemic hit. I had already been sketching a little bit before the pandemic, but I never really had time because of full-time jobs, not having the resources. And then when the world really came to a pause, I was like, I’m going to go for it. I sent my dad messages, like, “Can you please send me books from Congolese art history . . . ” and three days later this heavy-ass box from Belgium came. All books. And I was grinding and reading and reading and calling my dad saying, “What did my Congolese grandma say? How do they live?” Digging so deep that I was like, This is it.

This is unique in itself, because this is me, who I am, my identity, and a person, and exploring my two cultures. So I don’t need to flip through magazines. I don’t need to look for inspiration.

Because the inspiration is “me.”

Right! The family, the culture, the things I don’t know yet . . . That kind of made it its own language. This new design language. By studying it, asking questions, then it morphed into these pieces that I’m so glad you can’t find in any magazine, not online, nowhere [laughs]. And that was so important for me. I don’t want to have pieces that look like another designer or that they might aspire to or look similar. Some people said, “Looks like Art Nouveau.” And I said, “Well, jackpot.” Because Art Nouveau in the nineteenth century was derived from . . . you know, the whole spiel. But I think that’s when I kind of found my love and I was like, This is great because I can self-express through something I love.

Someone asked me, “What is your form of self expression?” I said, “These pieces of furniture.” I’m discovering my identity more, my heritage, and I’m pushing it out through furniture as opposed to speaking about it. To me, that’s a great weight because I’m still discovering and still learning, and I think it will never stop, you know?

Living room style lobby

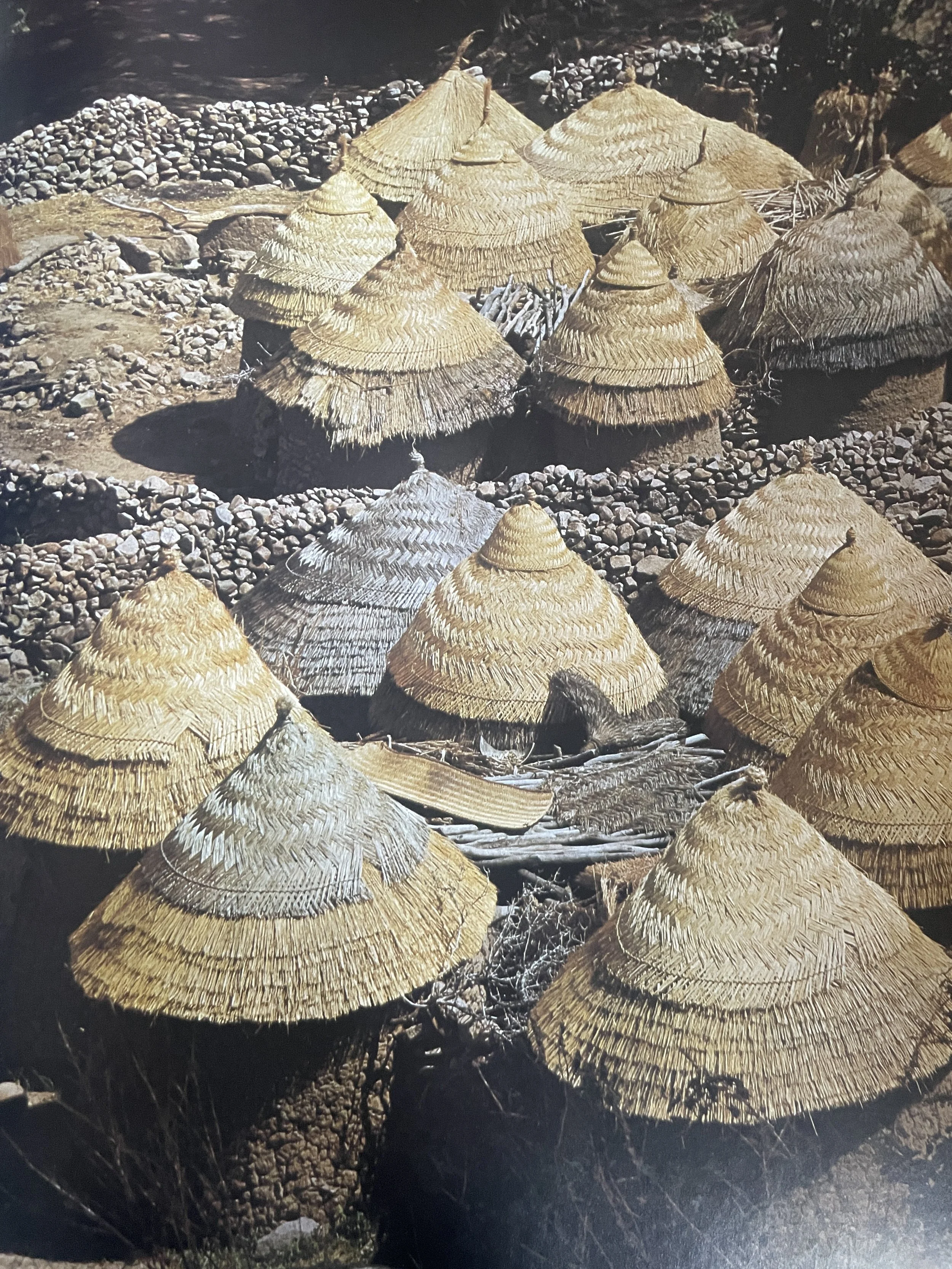

Traditional Congolese clay architecture, courtesy Kim Mupangilaï

What inspires you?

My appreciation for different cultures and traveling. And that doesn’t have to do anything with design. It can be a produce market, certain textures and colors that people in different countries are wearing when I’m traveling, ancient architecture.

I rarely flip through books for inspiration. I don’t know why, but I feel like I can’t be my unique self if I’m looking at, let’s say, an interior that already exists. I can absolutely appreciate it, because some are gorgeous, but I don’t want to recreate something. Totally hate that.

What do you do to get out of a creative rut?

Going on a long walk. I love cooking. Things that have nothing to do with design. Strolling. Just, you know, listening to podcasts and walking for hours. Reading. Maybe even going on a run. Very simple stuff.

You can’t force creativity. That’s such a hard lesson.

Oh, yeah, I learned that as well. Being creative on command is so much harder than letting it come to you, you know? Sometimes we have to, which isn’t smart.

“Surreal,” “organic,” and “whimsical” are three words I would use to describe your work. How would you describe your work?

I think you’re accurate. Those three words are great. Someone once said that the pieces appear to be dancing. Rhythm is so important in Congolese culture that I wanted to articulate that in the work. And then someone else said to me it almost feels like the pieces are so surreal from afar, and then when you look closer, they’re so intricate, and you see all these little details. To me it can be compared to someone’s identity―once you look closer, you start to understand people’s identity and goals. I was like, “That’s a really nice way of looking at it. That’s kind of what it’s about: identity agreeing cultural landscape.”

If I had to add another word, it would be “playful.”

Mm-hmm!

But when you look closer, as you said―in particular, when you open the armoire, the design of the hinges is such a beautiful thing. There’s something special. Very handcrafted, at that small level.

I love that you receive it that way. Absolutely.

What’s next for you and your business?

Well, one of my dreams―which again, I’m dreaming big―has always been to work with a museum or have some pieces in a museum. And to work with curators in that museum on cross-cultural design, vernacular design. It’s nice to design things but have a voice, some sort of representation, like teaching or working with museums, where you can reach a broader public. That’s something I would love to do. Of course, I don’t know if that’ll ever happen, but knock on wood, gotta believe it.

Designing more pieces, because people are like, “Oh, I can’t wait to see other things you design.” And I’m like, Wait a second, I just brought all this stuff out. What’s next, already? Give me a break [laughs]. I guess see if I can stay afloat, or work in the supermarket or not, you know [laughs]. I’m kidding . . . whatever I’ve got to do. I think I’m just very curious to see where this part of designing takes me, and if I can go that little level up, as in, make it mean something more than just something nice to look at. That’s what I’m really hoping for.

Do you feel like you’re part of the New York designcommunity? Do you roll with an artistic circle?

I find that a really, really good question. I definitely know that there is a circle. And there are circles. I think I probably know most of them in those circles, but it’s not like I roll with them. Usually there’s a gallery opening, or someone’s doing a show, and those people end up also at that show, because we all have the same interests, but it’s not like, “OK, let’s all ten of us go.” I guess in that sense, I’m kind of a little loner. Do my own thing, you know. But I appreciate them all. I think it is very prevalent that there are certain―not cliques in the negative sense―but cliques of the designers, and they always roll together. And I noticed that as well. But before, I was like, Oh, these people must just be friends.

In one sense, it’s good, because that allows your work to not seem derivative at all.

Yes.

It’s so clear that it has its own vision and comes from your own influences, which is part of why I reached out to you. Your work is so refreshingly different. Finally, it’s not plywood done for the ninetieth time!

Oh, god, I’m so glad you say that.

How did you transition from working at firms to doing your own projects?

My first interior project I did simultaneously while working full time because I was like, I just got to New York, how am I gonna live? That was just the first seed that was planted. I was like, It’s kind of nice to have this creative control, but also, no one knows me. It’s hard to get solo projects, you know? So I’ll keep working, and if something comes my way I’ll do that as well. But I think I started to pull back from working in design firms and architecture firms because I felt like I couldn’t really push my own creativity out because it was all going towards the firm. I kind of didn’t like being creative anymore because my whole vision was, “Ooh, creating! Nine to five! No . . . nine to, like, freakin’ 3 a.m.” I said, “Hey, maybe I should do something less time-involved and keep that creativity for my own projects.”

And that’s how I went into solo practice. Someone reached out to me also during the pandemic, [asking] if I wanted to do their house upstate. So many people were leaving the city, buying houses upstate. So that was great.

It also gave me more time to really think about furniture stuff. I think that’s kind of how it came to life. Obviously a little bit of stress here and there. But with the gallery and a whole PR team, that kind of blew it up. So in that sense, I was like, OK, now at least my name was a little bit out there, and hopefully I can financially keep supporting it. Because it’s all essentially fate, you know. But at the end of the day, I don’t want to look back and be like, Ugh, I always wanted to do that. Just do it. You know?!

So now are you a sole practitioner, or do you have a team?

No team. Now I’m focused on the furniture pieces. I’ll be working with this gallery for two years. I have to bring new designs every quarter of the year. It takes time for me. I can’t develop something in a week. Some designs took me three to four months. That’s my focus now. But at the same time, I’m like, Maybe I should get a job so I can support all this. Something that maybe does not have too much to do with design, so I can fund my real passion.

What is the biggest challenge for running this type of business?

Knowing that in the very beginning it’s basically 100% self-funded. Which was challenging and very scary. But then I’m like, What else are you going to spend your money on if it’s not for your passion?

Up to 2021 or 2022 I felt comfortable. I saved a little, [then thought] I’m going to take that leap of faith. I think that’s been the challenging part, keeping it sustainable after the fact you dropped something. It’s all nice to look at the beautiful pieces, but hopefully the cents have to come back to me. So that’s the scary part.

And everything comes in waves. Sometimes people are like, “Oh my god, I’m in a big spending mood.” Then sometimes, like the summer, because people were stuck for so long, they’re spending their money on traveling. Which is understandable. I’ve heard from a lot of other designers it’s been a very strange kind of summer, saleswise. But I think that makes sense.

Where can people experience your work?

In Greenpoint, Ponyboy bar. I think it’s changed over the years, like they added things. It’s actually open for five years today. They’re celebrating, so I’m like, Oh my God. I didn’t fuck up, you know? Then [a home I am designing] upstate is still in the works. I worked on that project for two years.

My main focus is the furniture, but I would love to design residential spaces, restaurants. But that’s been pushed a little bit on the back. Everything was on view at Superhouse gallery. And every piece is for sale through them.

What’s the best place in New York to get a housewarming gift?

Primary Essentials, Dashi Okume, LES Collection, and Gohar World.

What are the vintage sellers, concept stores, and designers in New York to know?

Chickee’s; Mirth; Vaux; Malin Landeus; Form Ate-lier; Friends of Form; Lichen; Portmanteau; Somerset House; Sincerely, Tommy; Primary Essentials; Dashi Okume; Shaina Tabak; Minjae Kim; Sarah Burns; Cassandra Mayela; and Conie Vallese.